Zhong Nanshan was nearly 36 years old by the time when, unbeknown to himself, he met two major turning points in his life. In September, 1971, when Zhong returned to Guangzhou from Beijing, and for some time afterward, he felt his father's anxi ety. What was his father worried about? He dared not ask. Until one day, in mediation, his father asked him, “Nanshan, how old are you now?” Not knowing what his father meant, he replied that he was thirty-six. “Oh, already thirty-six. That's terrible”, his father sighed deeply. With his father's words in his mind, Zhong was determined to set the Thames on fire someday. This was the f irst turning point in his life.

The second turning point happened shortly after he arrived at the hospital, where Zhong misdiagnosed a patient who coughed up black and red blood with tuberculosis, and who the next day was found to have hematemesis of the digestive tract, which nearly kil led the patient. This experience greatly influenced Zhong, and he began to study medicine more intensely. Eight months later, Zhong Nanshan had written four notebooks full of notes and had become an expert in emergency care, with doctors at the hospital praising Zhong as “worthy enough to be an attending doctor.”

In 1979, Zhong was appointed director of Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Diseases.

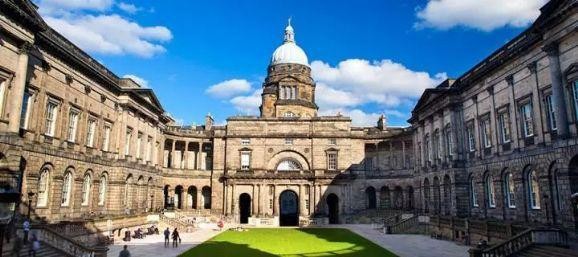

More impressively, in the same year, Zhong Nanshan obtained government-fund support and attended the Universit y of Edinburgh to further his studies. He was 43 years old at that time.

Fig 11: University of Edinburgh where Zhong furthered his study abroad

Zhong Nanshan arrived in London on October 28, 1979. Before long, he received a letter from his preceptor, Pr ofessor Fleury, head of the department of respiratory sciences at the Royal Hospital of Edinburgh. “You should be aware that your qualifications as a doctor in China are not acceptable under British law, so you are not allowed to do clinical work. You can only visit laboratories or wards here,” the letter stated. “In this case, it will be suitable for you to stay here for no longer than eight months.” Zhong Nanshan felt like a ladle of cold water had been poured on him, because of this unexpected piece of advice.

Zhong Nanshan did not lose heart despite his preceptor's words and the indifference of his peers. Instead, he determined to make the most of his situation. He started from inspecting the wards, where his insights and extensive knowledge soon gained the attention of his peers. On one of his rounds, he encountered a patient suffering from pulmonary heart disease with sub-respiratory failure and refractory dropsy. Although doctors had been using diuretics for a week, the patient’s edema had not subsid ed and his life was in danger. After analyzing the patient’s medical history, Zhong Nanshan used TCM syndrome differentiation to diagnose the patient as having metabolic alkalosis. Zhong proposed a different and controversial treatment, over which doctors were at loggerhead for a while. Unable to reach a consensus, they were forced to wait for Mr. Fleury's decision. Half-thinking, with a complicated look at the obdurate Chinese doctor in front of him, Professor Fleury instructed a nurse to take a blood test for this patient. The result showed that the patient did suffer from metabolic alkalosis. Without hesitation, Mr. Fleury gave instructions: “Follow the treatment plan of Zhong Nanshan, the Chinese doctor.”

After four days of treatment, the patient finally recovered. “Get to know the C hinese again,” Zhong's British peers all said. It was not until then that his British counterparts began to have trust in him and cooperate with him.

On another occasion, Zhong Nanshan spotted a problem with a project related to smoking cessation when he questioned the results derived by his preceptor. Zhong immediately decided to conduct experiments to test these results. Regardless of the risk to his own life, he experimented directly on himself by inhaling carbon monoxide and then testing his blood. Three months later, his paper overturned his preceptor's conclusion and was recommended by his supervisor to be published by the British Medical Council. Since then, Zhong has established several principles for himself: Fear no authority, tell the truth, and respect evidence.

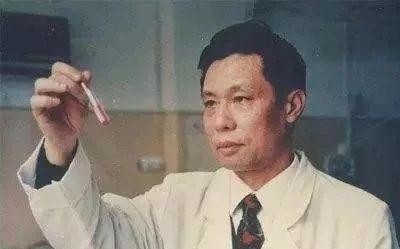

Fig 12: Zhong Nanshan in the laboratory

At the University of Edinburgh, Zhong Nanshan specialized in the prevention and treatment of respiratory diseases. He made six important achievements and published seven academic papers, and presented at meetings of the Research Association, the Society of Anesthesiology and the Society of Diabetes of British Medical College.When Zhong finishe d two years of study, Professor Fleury repeatedly asked him to stay and work in the UK, but he was determined to return to China and render good service in his homeland. He said, “It is China that sent me to the UK. My motherland is now in need of me, and my career is in China.” After returning from the UK, Zhong resumed his work at Guangzhou Medical College where he was elected an academician of the Chinese Academy of Engineering in 1996.

Fig 13: Academician Zhong Nanshan